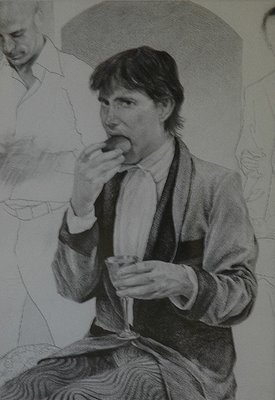

Malodorous Crumpet by James Huctwith

Malodorous Crumpet by James HuctwithIts an odd feeling looking at yourself in a painting or in a drawing. Unlike a photograph, which in most cases is so hastily devised that it doesn't possess any spirit of the sitter at all, a painting or drawing requires an almost psychic bond between the sitter and the artist. The same bond that connects actor and audience in a theatre must also needs exist for the painter and his subject.

It doesn't happen very often any more, this connection, as few people possess the skill or training to manage drawing or painting on this scale, and a lot of people simply cannot afford to have it done. At one time of course, before the advent of photography, it was de rigueur for people from the haute monde to have their portrait painted, not once, but several times. Titian, Carravaggio, Michelangelo, Davinci, Rembrandt down through to Whistler, Carrington and Augustus John all made their livelihoods and legends by painting other people. Extraordinary, isn't it?

My friend James Huctwith, is an heir to that fastly disappearing breed of artist. How much more equally extraordinary is that the necessary bonding to his subjects are done from photographs of them, endlessly perused and studied and turned inside out, to achieve EXACTLY the right sense of truth that matches the shadowy ideal in his mind's eye.

James is a classically trained artist of what one might term "the old school". Its not surprising then that one of his greatest heroes is Carravaggio and that his knowledge of Old Masters and their works could fill several shelves of art history texts (although I suspect James' versions would be a whole lot more raunchier and fun). He is probably one of the few working at the level of portraiture (if I can use such a term, not being an art critic, I'm probably making a tonne of errors) of the old Masters in this country, right now. His skill set is exemplary, and he has mastered his technique to a degree that he doesn't even have to consider it that much. He works on it constantly, and for him, a lot of the technique is about expediency. How to manage the paints and colours in ways that will let the work get done faster? It isn't a question of painting itself in that sense, but the technical knowing inside and out of how the concept of colour and composition work. He knows how to accomplish what he needs to do technically. The question that plagues him (as it plagues all artists of any merit) is, can he live up to the chimera that exists only in his head?

James can and has painted architecture and flora and fauna with equal ease, and yet I suspect that his heart truly lies here; in the mysterious shades and soul baring brightness of the masculine gay world he knows and loves so well; in bringing the masculine form to an incandescence on canvas that hasn't been explored for several centuries.

He's painted I think, almost all of his friends, in various and sundry motifs from dark and violent to light and romantic. I think I am one of the few whose portraits are exercises in fey, piquant fun, free of the darker tincts of feeling that run riot in a lot of his work. If you're familiar with James' ouvre, then you'll know that it can have a shocking Pan-sexuality, a no-holds-barred, take-no-prisoners kind of intensity about it. Whether its a wasted youth in the throes of a drug induced nightmare, or an orgy with bodies hanging off meathooks, or a leather daddy playing with his toys, there is an aura of exhausted, raw sexuality in his work. Yet, on closer analysis, there is an almost over reaching, haunted sense of longing in there as well.

I suspect that what makes the paintings so human and memorable (and not just the naked bits!), is that James has somehow managed to capture on canvas the souls of his subjects. Through some sort of mysterious alchemy he takes the most ordinary of us (not all of us are as beautiful as some of his subjects) and gives us a stature that he sees or imagines in us. Consequently, we are transmuted from lead into gold through his devotion to the ideal of us in his head. He loves his subjects in a sense that Michelangelo must have loved the David, or the Pieta. I don't mean the models themselves, but the heightened sense of them as he sees them, and as they must be conveyed on canvas. James sees things in his subjects that may or may not really be there. He conveys his dark romantic nature through their eyes, and as we look back out at ourselves we see things we hadn't thought were there, and maybe never were. But this in itself hardly matters at all; reality is expendable in art. Which is fine; all that really matters as a result of this transformation is great art. With the work of James Huctwith, that is the final and greatest achievement.

1 comment:

Well, Trevor, I think you just bought your "can do no wrong" ticket from me.

Post a Comment